36 Questions to Save the Nation: Part 1

Whether we're organizing our friends against our enemies, turning our enemies into our friends, or simply hauling ourselves off of the couch, no single one of us can do this work alone. I was given a PhD, probably in part so that I would hurry up and leave, but also in part because I discovered a few new things about how to create the social fabric that everyone says is collapsing. In this short series, I will talk about what I learned, why it matters, and what we need to do with it next.

There have been many “before and after” events in my life, but this remains one of the clearest. When I was 22, I read Robert Putnam's book Bowling Alone. And when I finished, I knew that I would be a social scientist.

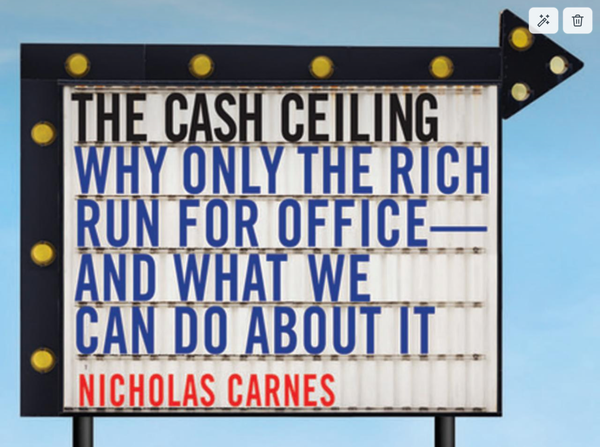

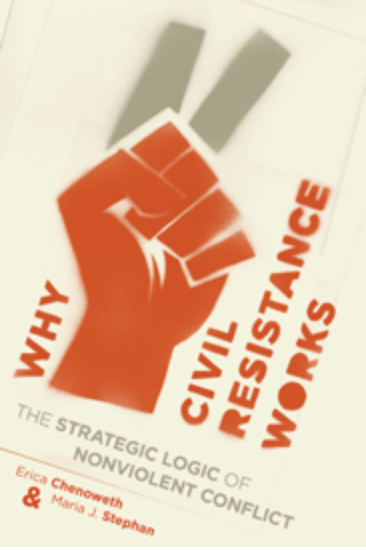

I had already been looking for Big problems to solve for quite a few years, and the first thing that gripped me was the scale of the problem Putnam was describing. The book was about a trend that affected the entire United States, and that had been happening unchecked since the 1960s. The second was the severity of its consequences: Americans were simply not taking part in their country like they used to, not voting, not reading the news, not volunteering, not running for office. At the time, few people would see so far down the road, but I view these now as simply the precursors to what we are experiencing today: a wholesale rejection of both the practice of voting itself, and the very idea of civil society. But the third reason I found Putnam's work so gripping was the incredibly simple explanation that he gave for this catastrophe: we just weren’t being social anymore. And everything was falling apart because of it. I was hooked.

As a quick aside: If you want to know more about Putnam and his work, which I strongly recommend, then I would actually recommend you start with Pete Davis’ biography Join or Die. I interview Pete about it both here and here. Bowling Alone itself is seminal, but it’s also written by a man who used to be the head of the American Political Science Association, and it feels like it — 400 pages of re-stating assumptions, testing a large range of very similar hypotheses, and interpreting regressions. By all means give it a try, but if you can’t get into it I might go for the follow-up, Better Together. Instead of a doorstop worth of theory, this is a series of case studies showing the strength and importance of friendships in important real-world scenarios, including a successful unionization effort in a previously un-unionizable workplace.

But Putnam isn’t the story here, for a simple reason: we know things are falling apart now. What we need is something to put them back together.

Almost ten years later, I was deep in graduate school and well on my way to becoming that social scientist that Bob had inspired. But instead of doing what most scientists did, which was passively measuring the effects of existing relationships, I decided I would actually try to turn the tide. I wanted to study how you created friendship. The problem — and the reason that nobody else studied it — was that this was really hard.

If you’ve ever participated in a psychology study, then you’ve gotten a glimpse into this difficulty. You came in, you played a little game, it took ten minutes, they gave you ten dollars, and you never thought about it again. The interaction was fast, easy, and small — because otherwise, either you wouldn’t have done it, or they wouldn’t have had enough money to pay you for it. And if you’ve ever participated in a friendship, then you’ve gotten a glimpse into how much different they are: hours and hours of time spent together, over years, in difference places, doing different things, often with many other people. Just about the opposite of participating in a psych experiment.

There were some researchers who had tried to use their normal tools on this, but that meant doing things like sending people text messages to be more social, and then being disappointed when nothing happened. More ambitious researchers had done studies of college roommates, and gotten very interesting results, but this wasn’t very useful to anyone else, because I couldn’t tell two people to go live together for a year. I decided that I needed to develop an approach that anybody could use — like text-messages — but that was large enough to actually make a difference — like one-room double-occupancy dormitories. So rather than start with something that was definitely small, I started with something that definitely worked: a paper titled, “The Experimental Generation of Interpersonal Closeness.” Or as you probably know it: The 36 Questions to Fall in Love.

The 36 Questions were first (I believe) popularized in the NYTimes Modern Love column, an “origin” which has made them sound slightly less serious than they are. The original research was published, with five co-authors, in the Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin in 1997. In it, pairs of randomly selected strangers are simply asked to read from a list of questions such as the relatively benign

Before making a telephone call, do you ever rehearse what you are going to say? Why?

Up to the almost excruciatingly intimate,

If you were to die this evening with no opportunity to communicate with anyone, what would you most regret not having told someone? Why haven't you told them yet?

The whole process took about an hour, but at the end, the two people who had read and answered questions together often felt they were as close to one another as to friends they had known for years. I decided this had to be my way forward. (And honestly if you had to read just one of the things I've mentioned, I think it should be this paper, which is only 15 pages long.)

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0146167297234003

Through luck, generosity, the simple choice to attempt something ambitious and, of course, the help of several close friends, I was living in Baltimore. I was doing my dissertation at a school that wanted to improve relationships between its parents, and its teachers, and that was prepared for me to try something new: a set of structured questions, designed not to produce romance, but a supportive educational environment.

I started by taking a very close look at the 36 questions, and after I had read through them a few times, I thought I saw a pattern: the questions fell into roughly four categories.

- Strengths: What are you good at?

- Difficulties: What are you not very good at?

- Aspirations: What do you want to achieve?

- Priorities: What is most important to you?

I then re-framed these for the context: What are you good at ... as a teacher? What are you good at ... as a parent? What do I need help with ... that you, as a parent, could help me with? And I recruited teachers to walk through these questions when they were introducing themselves to parents for the first time.

The very long story very short is that they worked, and some of the teachers loved them, but the impact wasn't enormous. In fact, this was fairly consistent with similar work that I'd read. The intervention had probably created stronger relationships, but until some event happened that required that stronger relationship, such as the student or family going through something difficult, it wasn't going to make a difference. A safety net isn't helpful until you fall.

But in fact, the experiment had been an enormous success – because it excited an expert, who was going to make it dramatically better.

This story is longer than I expected it to be! Tune in for Part 2 next Thursday.

If you made it this far, and you haven't subscribed yet, I'd like to ask as a personal favor that you please subscribe, and share the newsletter with people you know. If I don't know that someone is listening, I have no reason to keep writing – and if I can't pay my rent, I have no ability to keep writing. With my profound gratitude to everyone, both paid and free.

And if we make it to Sunday, I'll see you Sunday.