Influence is good and we should use it: Part 1

(Note: I’m very excited to get to the How and When arguments of my planned series, but they both require my getting through a rather long book first. Which is just to say that there are logistical hurdles, but they are specific and known, I haven’t forgotten about it.)

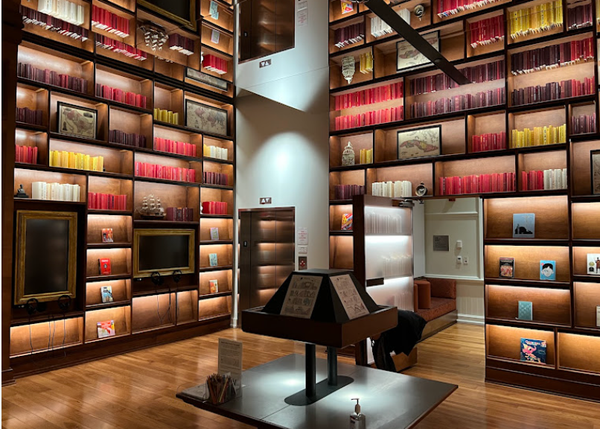

As tanks are shipped into Washington, layers of fencing begin to wrap around the National Mall, and everyone in the city prepares to hold their collective breaths for this weekend — I thought I would write about one of my favorite books. It’s called: Influence.

It’s a favorite in part because at least for me, it manages to feel both familiar and adventursome at once. It’s a book written by a professor, Robert Cialdini, about the peer-reviewed research that he and other people have done. This is territory on which I feel at home. But this research is into the much less academic world of: getting people to do stuff. Of influencing them. A world that, with all my years of passive research, feels almost totally alien to me. When you spend your career trying just to understand how things work, then changing them can feel unfamiliar, or even inappropriate. Vulgar. A job for someone else.

But it is a world that we all need to inhabit, now. We cannot be content to simply observe, or even comment upon the things that are happening in front of us. Federal troops in Los Angeles. The unashamed rejection of due process. A military procession through the nation’s capitol for the president’s birthday, as if we were North Korea. “Third world bullshit,” in the words of the man who killed Osama Bin Laden. In these circumstances, we need to do things, and influence people to do things. And for those who need some bridge between knowing and doing — or if you just want to know how to influence better — this book is a great place to start.

“Influence” is not about the entire art of influence, but rather about the things that influence people *above and beyond a rational decision.* But that’s okay, because for people who are especially research-steeped, the rational part should be easy anyway. Offer someone a good deal, in good faith: they’ll take it. But that’s not the whole story. What the book describes are the tips and tricks and techniques that, the author claims, were used constantly and successfully against him by salesmen and spam callers, until he got so mad that he became one himself to learn their tricks. The darker side of influence, we can all acknowledge: but a no less powerful one. And when confronting power, we need — power. The principles he brought back fit neatly into six categories: Reciprocity, Consistency, Social Proof, Liking, Authority, and Scarcity. But the truly astounding thing about the book is just how deep each of these categories goes.

Principle 1: Reciprocity, or Social Obligation

Humans are fundamentally and profoundly social creatures. So pulling them into a relationship with you — of any kind — is an incredibly strong way to influence them. If you give somebody something — even something small, like a soda — they will feel more obligated to do something for you in return. Of course, if you only got out what you put in, there wouldn’t be much of an advantage here. The real trick is that even gifting something small – even when it’s not something the receiver actually wants — can have a spectacular impact. In the world of laboratory psychology, a free soda can dislodge a somewhat larger monetary donation. In the wild, a free sandwich from a pharmaceutical representative can help to dislodge six figures or more in drug sales from a doctor. You give me something — I give you something! And as Kahneman and Tversky showed, humans are exceptionally bad at comparing those “somethings” in a rigorous way, allowing for order of magnitude returns.

Principle 2: Commitment and Consistency, or Identity

Identity is a complicated thing, but I think of it in a fairly simple way. It’s the set of instructions that we have for ourselves about our own behavior. I am this kind of a person, so I do this kind of a thing. This is enormously valuable in a complicated world, where making an optimal decision can be essentially impossible. Instead, we just try to make decisions that are consistent with our identities, and we defend them so ferociously because having clarity about how to act is of objectively immense value.

The tricky part is that, whether we think of it this way or not, identity is also very fluid, and influenceable. So there’s a very powerful approach in getting somebody to decide that something is a part of their identity, because then they’ll act like it! For example; ask someone if they’re the kind of person who is willing to volunteer. They’ll probably say yes, because they’re not actually committing to anything. But then if you ask them to actually volunteer the next day, they will be much more likely to. Maybe — and many of these effects admit multiple interpretations — because they actually think it’s part of their identity and maybe because they don’t want to look like they lied to you. But either way, there’s a pressure to act in a way that’s consistent.

And most books would just leave it there. Cialdini sees that this behavior goes far beyond neighborhood cleanup events.

The difficult part of this approach is that if I just *tell* you what I want your identity to be, you’re probably going to ignore it, or even rebel. Identity is your concept of yourself, so you’re the final gatekeeper on what it means. But many people have figured out how to incept identities past these defenses — like the Chinese soldiers running POW camps during the Korean War. Rather than just tell American GIs that communism was good and capitalism was bad (which would be rejected as too obvious), they asked them to write essays about the things that *might* be bad about the US system, and the things that *might* make sense about the Chinese one. And in exchange they got something small, like an apple. Because the Americans hadn’t been forced, and because the prize was so small they couldn’t easily claim they’d just done it for the fruit, this turned out to be an incredibly effective way of changing minds. If it wasn’t forced, then it couldn’t have been faked, and so I guess I do really believe these things — huh. Or at least that’s how the book tells it.

I’m more inclined to interpret this another way, which is that the GIs were politely asked to consider a new perspective, lowered their defenses, and found something they truly agreed with — but that doesn’t make the effect any less impressive. However you want to read it though, I am particularly driven to share this example because I know with total certainty that it’s also been tried on me — and I found it shockingly effective, even while being fully aware of the intent, and having already read this book. Many years ago, an advisor wanted me to do research on Twitter, which I found to be a complete waste of time. I guess this was clear (possibly because I said so out loud) so without providing any obvious reason, she asked me to write a short paper on the abstract idea of how social media data might be used for something valuable. Well, I did — and suddenly, to my total and still embarrassed astonishment, I saw all sorts of advantages that I’d never considered before! That probably did get me through the next few months, though it’s also the case that if I ran away from that lab and never looked back as soon as I possibly could. Which is itself a helpful reminder of the flexibility, and limits, of any of these ideas. But even if they only work at “the margin” — it’s still a remarkably large margin.

Principle 3: Social Proof, or Network Inertia

The principle here is pretty straight forward. Human’s innate social character can make it quite hard for them to act differently from large numbers of other people. But if you want to influence somebody, then demonstrating a behavior can be a remarkably effective way of getting them to do it as well. Not just for picking up trash, but for deep and irrational behaviors like phobias, as well. Scared of spiders? Watch a video of someone else handling them!

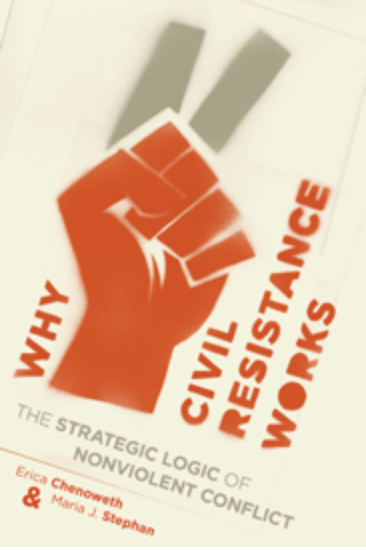

Cialdini makes it clear that this can have terrible consequences — copycat suicides, cult behaviors, etc, all of which are especially powerful when the bad behavior is the *only* one people are exposed to. This is the reason cults cut people off from their sane, well-meaning networks — examples of non-cult behavior make it much easier to resist following along. But I find these less compelling because the same principles apply when using it for something positive. Don’t think of yourself as being “the only person who wants to protest.” Think of yourself as “the person who is going to show everyone else it’s okay to protest.” Or to resist, or to simply point at the naked emperor. You should never underestimate how powerful that is for the people watching you.

To be continued

On Saturday!