Influence is good and we should use it: Part 2

See Part 1 here!

Principle 4: Liking, or Positive Associations

If you like somebody, you’re more likely to do something for them. But why do we like people? One bad but incredibly common academic assumption is that it’s largely a function of familiarity. If you’re around someone a lot, well, you’ll grow to like them. But if every experience you have with that person is bad, then exposure will actually have the opposite effect. The example Cialdini gives (which, working from years-old notes, I did not record a citation for) is of school desegregation. Done naively, it has the potential to make relationships worse. Unguided unfamiliarity leads to misunderstandings, leads to conflict, leads to a cycle of negative associations. Instead, it’s important to craft situations where students have a good time, together. One especially effective technique is assigning people to work together towards a positive goal – a lesson that has implications far beyond schools. But as just one possible example of many, I remember a sociology professor taking one look at a friendship network and knowing who the athletes were in a high school, because the group was so deeply and uniquely integrated.

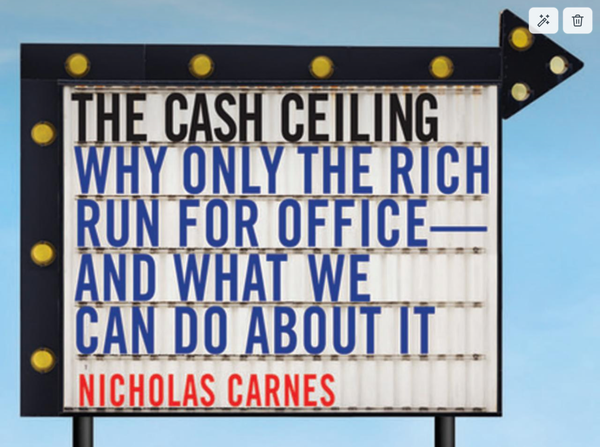

I think this principle is most important to consider when it comes to politics, volunteering, and similar activism. You don’t get into it, just because you do it a lot. To be honest, my most recent experience in the field came close to definitively killing my interest in organizing. But if we can start with positive associations, people will be more likely to sign up for very different, much harder jobs in the same space. Like the theme that came up at my social capital brunch, joining comes before belief.

Principle 5: Authority

Stanley Milgram, whose groundbreaking research got participants to commit fake murder, effectively demonstrated that humans will do just about anything they’re told — under the right circumstances. But what’s often left out of the retelling is that they won’t do it for just anybody. These experiments were not about just any obedience, but about obedience to authority. Study subjects would continue to do horrible things when they were told by the stern, lab-coated, clipboard-carrying Director of the study — someone with the Title, Clothes, and Trappings, of authority. (And, someone they had already agreed to obey, activating their drive for Consistency/Identity.) But when the man in the study who was pretending to be tortured asked the participant to stop shocking him, they didn’t obey. He just didn’t carry the same weight.

Again, a principle that can be famously badly abused. But also one that simply has an objective power to it, that we ignore at our peril. If you want people to treat you like an authority, Title, Clothes, and Trappings (meaning physical indicators like a clipboard, watch, car, etc.) can make a shockingly large difference.

Principle 6: Scarcity, or Competition

The last principle is the strangest. When people think something is scarce (either naturally or because other people want to take it), they value it more. On one hand, this makes sense for things like water. On the other, it leads people to ascribe almost magical properties to discontinued products. If a detergent is pulled from the shelves because it’s been banned, people will start believing it was actually better than the un-banned products. When a judge asks that evidence be removed from consideration in a trial, people will actually pay more attention to it. The often subconscious reasoning is, It must be valuable if somebody wants to take it from me! But like all of these principles, even if it doesn’t make sense, it’s powerful.

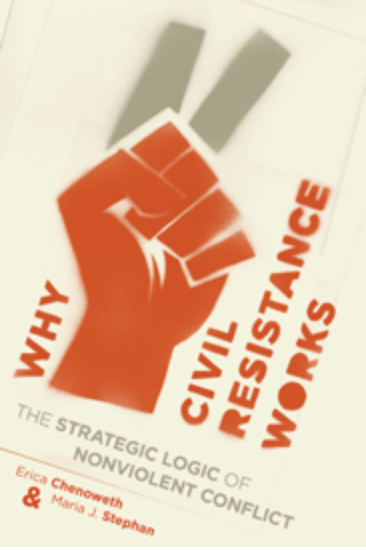

So powerful in fact that it may have changed the course of history — and may still again. Cialdini argues that in the Soviet Union, the policies of Glasnost and Perestroika reintroduced some old, lost, freedoms. Then they were taken away again. And even if, really, things were just going back to the way they had been before, there was suddenly massive resistance, that had not accompanied the early state of affairs. He argues that by returning them, and then removing them, these freedoms were given the sheen of a resource that was too good to lose.

If you’re not convinced, there were very similar dynamics prior to the Tiananmen Square massacre in China. It started with the Democracy Wall movement — which led to a government opening — and then a shocked government retreat from that opening, seeing the enormous demand for more freedoms — and the enormous, ultimately tragic protests, in loose response to that reversal.

Which, finally, brings me back to the tanks.

In conclusion

If many of these essays feel like pep-talks to myself, well — that makes you a very insightful reader. But I am confident that if I need pep, I can’t be the only one. Getting people to do things, whether through ethos, logos, coercion, bribery, psychological hacks or just old-fashioned nagging, can feel incredibly daunting, foreign, and rude. But we must. We must. And to do so effectively, we (I) cannot think of it as dirty, or antisocial. What I am advocating is not for you to trick anyone into helping you. I am advocating that all of us — all of us — point ourselves at a greater good, and then help one another along towards that goal, using any and all of the tools at our disposal. Robert Cialdini devoted his life to recording some of those tools. I hope you have learned something from them.

And, that you go and use them today.