What Danish Children can Teach us about the Nazis

A little context

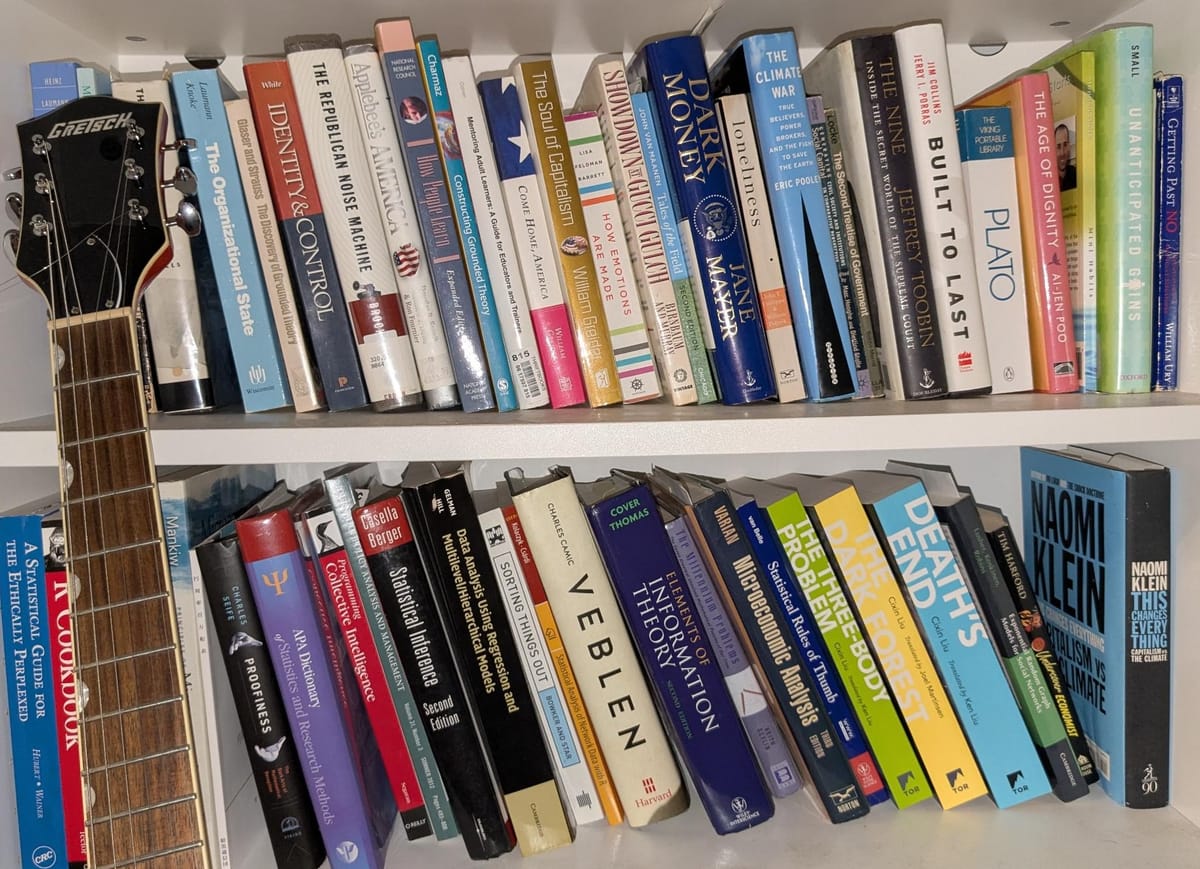

Since cancelling the serial installments from the long-form Plan, I'm still figuring out what content should replace it. I'm excited by the What Why How and When research, but it's also substantial work. To provide something that's easier but not trivial, I think it makes sense to draw on one of my other obsessions: books.

Apparently, I consume a non-fiction book every one to two weeks, which I know because I take notes on them. (Novels and musician's biographies are squeezed in between, but I consume them purely for transient enjoyment.) I manage to keep up this pace, and the notes, almost entirely because of our slow-walking dog. She drags me to the park for 45 minutes, and I take this opportunity to listen to an audiobook while texting myself notes on my phone. Between her intransigence, my insistence on being constantly productive, and the invention of noise-cancelling headphones, we've got a pretty good thing going.

Okay but how does this help you

As I imagine most of you understand, I could never estimate how much of a debt I owe to books. So much of what I know, and so much of what I believe to be my meaningful contributions, comes from collaging together the work of hundreds of other people. Especially now, when we need all the insight we can get, I thought it might be helpful to summarize and review books that I think are particularly important to the work that we're doing.

As Adam said in our last conversation, I have a "global opinion" – by which he meant, I have a very strong point of view about most things. Consequently, this is not intended to be an objective description of anything, but rather an argument about how the information in these books is helpful to us, now (or, total horseshit – but I tend not to finish those books). Even when it comes from very unexpected places, such as:

The Danish Secret to Happy Kids: How the Viking Way of Raising Children Makes them Happier, Healthier, and More Independent

(Which you can buy here, and in the widget at the top of the post.)

Briefly, the premise: the author Helen Russell, a British woman, moves to Denmark with her (also British) husband and their three (increasingly Danish) children, and writes about the experience. It has the tone of a magazine piece, and is constantly and cozily narrative, but her editorial eye is very sharp. The subjects she chooses and the additional, non-personal research that she does into them were consistently fascinating. But they are also not just a glimpse into any old country.

They're number two!

As of March 20, 2025, Denmark is officially ranked second in the world for life satisfaction, just a fraction of a point behind current leader and historically most-winningest country, Finland. However when I read this book, they were first, and they've never been far from the top.

I have always trusted this ranking (though it is not without challenges, several recently in the news, which we will discuss in detail soon). It is based not on an economist deciding that the cold is good for you, and consequently Denmark is Happy. Rather, it is based on the Danish themselves reflecting upon their own lives, via a survey question that has become the world standard after sixty years of kicking its tires. The Danish said We are, oh, about this satisfied – and congratulations, it turns out that's (second) higher than anybody else said about themselves.

I find this important to emphasize because I frequently encounter quite basic misconceptions about the nature of these rankings. The Danish do not get any extra points added because there are (apparently) trampolines in the street, or just because they have government wellbeing programs. They just said they're more satisfied with their lives than everybody else did. And because sixty years of research shows this question translates remarkably well across languages cultures and regions, I believe them.

But a number can only tell you so much

I trusted the results, but I couldn't do much more with them. I spent six weeks in Sweden when I was 13, and I was enchanted by the amount of chocolate that was forced upon me, but that's really all I knew about Scandinavia. Hecklers of this research were constantly making confident and generous claims like "The Danish can't possibly be happy, they're just content being miserable," and I didn't have much specific evidence to push back with. So I picked up this book, hoping to get a comprehensive look into the country from someone whose perspective probably had a lot in common with mine.

And, to get to the point, it looked like paradise.

But also a fascinatingly different paradise than I was expecting.

A bizarre mixture of Left and Right fantasies

There are the things that progressives bring up constantly about Scandinavia, like an incredible social safety net, a highly respected teaching profession, and an extremely reasonable work week. But there were also the things that seemed like they came out of a Republican stump speech: the country full of knife-wielding elementary schoolers who were sent out into the woods to play during recess, then called back for naptime like free-range livestock. No obsessive parenting, no coddling, just The Way It Used To Be. (Though they are carefully watched by adults who have Master's degrees in early childhood education, and were employed at the eye-popping ratio of one for every three children, if I remember correctly – though that number has been rising.)

Similarly, family life sounds extremely ... let me say Basic but in a nice way. Suburban, even when it wasn't technically taking place in a suburb. There is such a well-developed cookout culture that there are sausages designed specifically to be eaten while the other sausages are still grilling. Everybody drinks, and everybody plays sports, and everybody (mothers and fathers) also has literally years of parental leave. They trust their elected officials, they spontaneously sing together, and they have extremely explicit sex education for very young children.

Now – with the spectacularly dark turn that Republican politics has taken in the last ... ... okay maybe since Nixon, I don't want to push too hard on the idea that what conservatives really care about is Family Values or Living Free. I do use the word "fantasy" with all of its connotations. But at a minimum, life in Denmark seemed to show that such a seemingly bizarro world – the one I feel I know best from pharmaceutical commercials – is really possible.

Though it might require a deeply traumatic national experience.

Forged in fire

Denmark was occupied by the Nazis from the very beginning of the war, though only seriously starting in 1943. I first learned about its significance from Hannah Arendt in Eichmann in Jerusalem, where she describes the unique Danish refusal to round up, or even legally distinguish, its Jewish population.

This passage from the book has remained a key component of my thought ever since, and is a lesson that many contemporary institutions, such as Harvard and the state of Maine, clearly understand well: you have to say No to unacceptable demands. Because a huge amount of the time, bullies cave.

More historical context doesn't change the core idea, but is still informative. Denmark wasn't a threat, militarily. They mostly produced food, which meant Germany had an incentive to be nice to them. And, the Nazis considered them Aryan – not a model on which everyone can rely. For much of the war, they were allowed to run their own government, and were considered by most of Europe as neutral.

But even when they were accepting Nazi demands, and they did, they fought every step of the way, socially shunned any Dane who joined the German forces, gave unparalleled intelligence to the British, and refused to cross their clearly delineated red lines. When they learned that Jewish Danes were to be rounded up anyway, the Danish government had them all evacuated to Sweden in an emergency operation. Their death toll was the lowest of any country in the war.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Denmark_in_World_War_II

So while there was clearly already a deep cultural antipathy to authoritarianism, the author makes it clear this was only reinforced by the occupation. And it is clear this same stance exists strongly today: profound respect for, and profound expectations of, every individual. Trust in people, and government, and a corresponding, earned, behavior from both.

And now, decades later, as real Nazis once again march the street of American cities, finally we have international evidence of what Denmark knew all along: the happiest people in the world are the ones who fought back.

In any event

I came out of the book with a number of other firm convictions as well. One, that the life satisfaction research really is tapping into something meaningful – and two, that the form of our vision for the future seems thin and colorless, compared to the truly profound cultural shifts that now seem necessary for our country to thrive. But the good news is, better worlds already exist, within our own. Our job now is to learn from them.