Step 2: The Word is Treason. Part 1

In a recent post, I outlined the What, Why, How, and When of the work in front of us. I said that we must remove Donald Trump from power, because of his attacks on the United States government, through peaceful mass refusal to comply until he resigns, and as soon as possible. I also said that I would go into depth on each of these.

Part 1 – The What – Can be found here.

Today, I'll explain The Why.

The Why is not necessarily the most morally egregious thing he has done. There are now hundreds of contenders, and choosing between them is both difficult and unnecessary. The Why is the rationale that we present. The thing we tell our representatives and put on our signs. It is the flag behind which we march.

There will always be many – we must at least try to have one

It should be clear that coordination around an action is not just important, but necessary. A million people around the White House at one time is very different than a million people in groups of five, every few minutes. While not quite as critical as a unified action, I think that having a single unifying reason for our actions is also enormously valuable. The more unified the front, the more powerful the message – and the more time and energy can be put into developing it. We want to speak with a single voice. And we want to be telling the best story that we have. If someone asks why we're doing this truly extraordinary thing, and they leave without feeling like they understand, they are not going to help us.

I realize that this itself could be contentious. We should – indeed we must – be a large tent. No one should ever be turned away because their reason is different than ours. And in fact when I was on the campaign, we did weekly trainings that helped people to develop their own reasons for the work they were doing. I'm supporting Kamala because ... I have a pre-existing condition. Because I've spent my entire life fighting for our right to choose. Because my husband is getting harassed in the street by random racists, and we need someone who understands what it's like to experience that. When they knocked on doors or made phone calls, they were encouraged not to tell our story, but to tell their story.

But I think this is different. A personal experience is enough of a reason to vote for someone. But your personal story is probably not compelling enough, on its own, to justify the removal of the American President. Even if you tell the story of how you arrived at your decision to support this movement – and you should – there needs to be a deeper reason upon which we all draw.

Given the enormity of the requirement, the list of potential such reasons seems quite short. It's worth considering them.

The contenders

There are a few criteria that such a story must meet. It must be:

- Evergreen (it can't be "the tariffs," because maybe he'll reverse them all)

- Inherently disqualifying (it can't be "he's violating norms" because that's neither illegal nor in all cases bad - we should really be violating a lot of norms ourselves right now)

- Easy to say and understand (I don't think it can be "seditious conspiracy" or "emoluments" or "Paragraph 3 of Section 6 of Article 4.")

- True (this should speak for itself).

I believe the main contenders following these criteria are:

- The Rule of Law: What he's done is illegal, according to American law, and this is the appropriate reaction – again, according to American law.

- He Betrayed Us: He told us he was going to help us – and in fact, he is hurting us. He lied about who he was to get this job, and now that he's shown he never meant it, he doesn't get to keep doing it.

- It's the Right Thing to Do: He's simply causing so much damage that this can't go on.

All of these have strengths, and all of these have weaknesses. What I find most compelling is the fact that there's a single word – not a phrase or a tale or a slogan, but a word – that tells all of these stories at once.

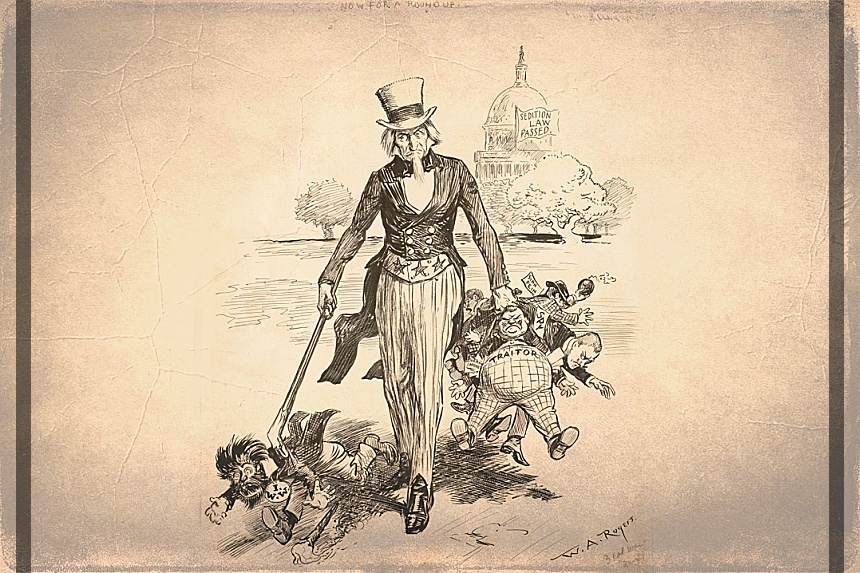

Treason

Author's note: this passage considers several cases and events already several years old, but that I found enlightening to finally examine in depth. If you followed the legal details of these cases when they happened, I hope it can at least be a helpful refresher.

The American Constitution describes the crime in just a few words. Here is the passage in its entirety.

Treason against the United States, shall consist only in levying War against them, or in adhering to their Enemies, giving them Aid and Comfort. No Person shall be convicted of Treason unless on the testimony of two Witnesses to the same overt Act, or on Confession in open Court.

It is so tightly defined because the British had used it to mean anything they wanted it to, and it had become a meaningless and vindictive catch-all. The Founders were very intentional about wanting to avoid a similar abuse. So Treason is placed in the Constitution itself, but narrowly scoped to just the acts that really, truly mattered. The acts so inexcusable, they required their own word.

Even ideas that seem simple can require some interpretation, but when the Constitution leaves out details, judges have filled them in. Writing in 1807, Chief Justice John Marshall defined "levying war," as well.

...if war be actually levied, that is, if a body of men be actually assembled for the purpose of effecting by force a treasonable purpose, all those who perform any part, however minute, or however remote from the scene of action, and who are actually leagued in the general conspiracy, are to be considered as traitors.

In other words, because the March to Save America actually happened – "a body of men [was] actually assembled" for the violent overthrow of the government – then the particular role of anyone in it is immaterial. If the judgment is against them, then they are all "to be considered as traitors." Including, above all, the sitting American President, Donald Trump.

Just ask The New Yorker

Writing in the immediate aftermath of January 6th, Harvard law professor Jeannie Suk Gerson quotes "treason scholar and law professor" Carlton F. W. Larson as saying “It’s very clear that would have been seen as ‘levying war.'"

The piece, worth reading in its entirety, goes on to say:

... a treason case against Trump himself might conceivably be built, if prosecutors could establish that he knew in advance that his supporters planned to violently assault the Capitol, rather than peacefully protest; that he intended his speech urging them to “fight harder” to spur them to attack Congress imminently; and that he purposely didn’t do anything to stop the insurrection while it was unfolding—or, worse, intentionally contributed to a security failure that led to the breach. Then Trump would have engaged in treason along with supporters who attempted, in his name, to overthrow the U.S. government.

And of course not long after there was precisely such evidence, of Donald Trump "intentionally contribut[ing] to a security breach."

But why was this argument not developed? In fact,

Why aren't other people even talking about this?

This isn't just my perception. Multiple articles make this same observation.

...a subject not much found in public discussion of the case: treason.

(From Mark Graber's piece in The Conversation, below.)

Since the Capitol insurrection, there has been little talk of treason charges.

(From Jeannie Suk Gersen's piece in the New Yorker piece above.)

The most straight-forward answer I've found is from David S. Cohen, law professor at Drexel, writing in Rolling Stone:

Were the rioters at the Capitol trying to actually overthrow the government? Or were they merely trying to disrupt a government function? All of this gets very complicated and would almost definitely bog down the trial, which is probably why the House impeachment team decided not to bring a specific treason charge and instead relied on the catch-all “high crimes and misdemeanors” charge. That’s a much safer bet.

In other words, as I understand it – yes any sane person would see that obviously, obviously, obviously, what every one of them committed was treason. But making the charge stick in court would be hard, because it depends fundamentally on intent, which is much more difficult to prove, so we went with the easier case – that also failed.

But as the President of the United States now engages in openly soliciting bribes from foreign powers – does "It was too hard" feel like the right rationale anymore?

I'm sorry, wait, that's the empty rhetorical horseshit sentence structure that people use to garner clicks, and avoid culpability. What I meant to say was:

Not bringing a case for treason was the wrong decision, because every available piece of evidence screams that this is the crime of which he is guilty. But what we're going to do about this fact, I'll have to get to next time.

Select References

The United States Constitution

https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/23pdf/23-719_19m2.pdf