That time I did a survey at a protest

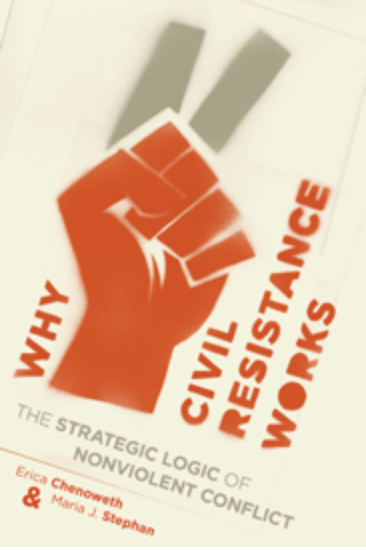

I have finished Erica Chenoweth's 2011 book, Why Civil Resistance Works, and I am excited to share what I learned. But as I transform my ten pages of notes from a series of texts that I sent myself while walking the dog, into an intelligent description of critical scholarship, I wanted to share my own experience studying social movements. At night, in the winter, on the streets of Pittsburgh.

I was young and energetic and in graduate school, and Black Lives Matter marches were happening across the country. I marched in New York, and was astonished by the vastness of the crowd – but I found myself even more fascinated by the motivations of the people who attended. Who were they? How did they come to be here? I stewed in this questions for weeks, until I had the opportunity to go to a second march in Pittsburgh, where by now I was determined, and bold, enough to actually look for answers. So I took my little notebook, and I wandered around the marchers, and I asked them the following questions:

- How old are you?

- What do you do for a living?

- How many people do you know at this protest?

- How did you hear about it?

- What do you think this protest will accomplish?

to which I added my own observations of race and sex.

What follows is not just my recollection, but a largely unedited description from twelve (!?!?!) years ago. It's rough and careless in ways I'd like to think I've improved upon over the years, but I also think there's something important in the energy of it. Rereading the adventure reminds me what it's like to Just Fucking Do Something when you think it's important, and this is a time to cultivate that energy again.

The Adventure

The first two questions were meant mostly as controls, and the fourth was more of a thing I'd heard before than a thing I really wanted to know. I had really wanted to ask "Why are you here?" hoping for a crisp answer like "My firm moral convictions," or "My friend dragged me," but the first person I tried that on gave us a three hundred word treatise that I felt compelled to pretend to be writing down, and I decided to change the question to something that at least didn't sound open-ended.

"How many people do you know here?" I was excited about though, given that I'm excited about social support and pressure and structure generally, and particularly when it comes to civic action. "What do you think this will accomplish?" felt almost perverse to include, as if I were asking it at a funeral, but it got closer to the question I'd hoped for of "What brought you here," and I was curious. And off we stormed, me and Jackie, just a buncha crazy kids with a dream.

Two hours and thirty six people later, here are a few of the things we knew:

1) Getting a representative sample is anything but straightforward

This had not occurred beforehand to me at all. The people who are easy to survey are also systematically different. An easy survey target is more physically isolated, not carrying a banner, and (especially and) not yelling anything. Tragically, every one of these things suggests that that they're probably also less ideologically committed, or at least that they're less socially embedded (which would have implications for the "how many people do you know" question). As a result of this, and my having difficulty overcoming a shyness of interrupting chants, we expect that our sample is a little older, a little whiter, a little less well connected, and a little less vociferous – whatever that's correlated with, in this case – than the complete population.

2) Still, people were exceptionally open to being approached

Maybe because this was a bunch of people who were out to be noticed – literally, yelling in the street – I think we were turned down twice, once by a guy who was "reporting for my school paper, and want[ed] to stay neutral." Almost everyone else was helpful if not, and they often were, friendly, and often gave much more detail than we asked for. In short, if you're thinking about this, and I hope you're thinking about it now, you should do it.

3) Even people at protests don't really know what protests are good for

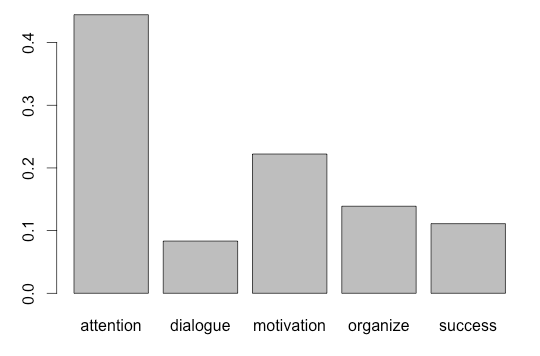

This was interesting. When I asked what people expected their marching to accomplish, they gave me a wide variety of answers that I crushed (slightly) into a number of categories that was small enough to analyze. These were:

- attention: meaning to the cause. ("Awareness" was a common answer, and it went in this bucket.)

- dialogue: Seemingly self-explanatory, but it was rarely specified between who and it didn't occur to me to ask.

- motivation: meaning for the people in the movement, i.e. marching was a way to increase member's commitment to the cause.

- organization: which was similar to 'motivation' in that it stressed this as a benefit for the marchers themselves, as opposed to the people watching the march.

- success: which I marked down for anyone who said they expected to see one of the things they were actually marching for, happen. We were marching against police brutality, and these people expected there would be less police brutality as a result.

Two charts summarize the numbers of people who gave which kinds of answers pretty well, but they don't capture how startled people tended to be by being asked about their expectations. "That's a good question" was something we heard a lot. "Well, I hope that ... " was another. Many people were visibly considering this for the first time.

But the charts: On the chart above, are the proportions of different answers, which explain themselves.

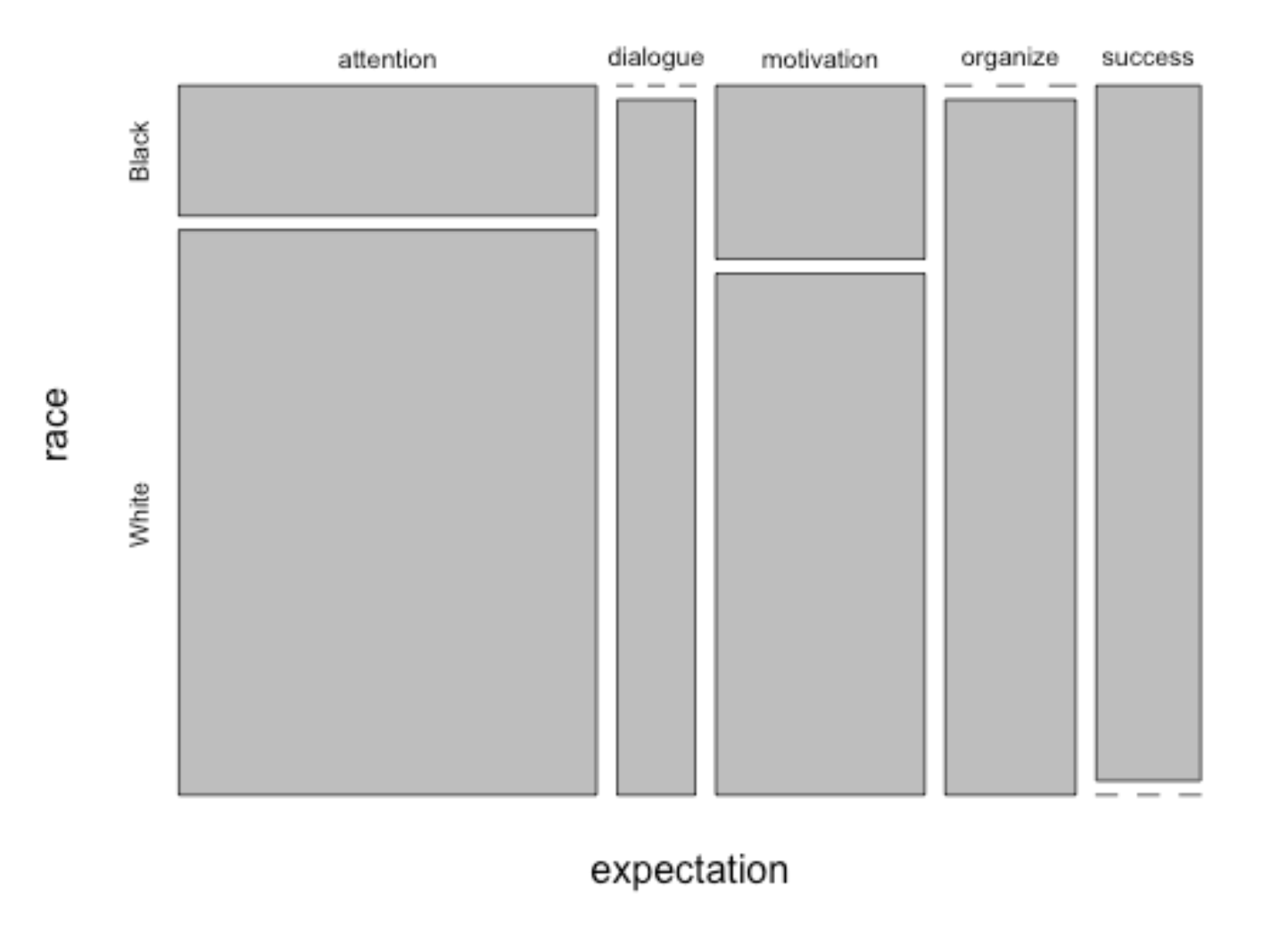

On the chart below however, the well-packed suitcase, the butcher's diagram of a chalkboard, the band insignia for Geriatric Flag, takes a little work. On the left, on the "race" axis, are "Black" and "White." On the top, along the "expectation" axis, are the categories of response for "expectation" – the same as on the first histogram. In each column, you can see the proportion of Black/White people who gave each kind of answer. The column on the left, for example, says that about four times as many White people said they expected the movement to get more attention, compared to Black people. In the far right column, by contrast, you can see that only Black people actually said they expected a concrete result to the protest ("success"). The dashed lines mean no-one of that race gave an answer in that category.

Before I dive in too deep: the whole sample was only 36 people, of whom only nine were Black. Describing nine samples of anything is not a recipe for confidence. Still, White people's interest in "awareness" has been a source of amusement for some time, and the complete racial split on "success" was surprising (as was the fact that only white people ever said they didn't expect anything would happen). All of that makes this hard to pass up completely.

My own interpretation of the split is that in fact, even when I was asking for expectations, people were actually describing something much closer to their hopes – and in turn, that their hopes were largely formed by their experiences with the thing we were talking about. I justify this by bringing up Economics-Nobelist-Psychologist Daniel Kahneman, who found that people often replace a difficult question, to which they don't know the answer, with a simpler one, that they can answer. "Who knows what will actually happen? But this is what I'm envisioning." Taking this one more step, (mostly White) people who don't actually feel the problem being protested, or experience it only in conversation, are saying that they hope the protest will have an effect on their experience of the problem – which is through conversation. It's not that they don't want the success (because otherwise, it would be hard to explain their presence) – it is however, or could be, that their experienced imaginations just don't make it all the way there. Whereas (mostly Black) people who experience profiling, discrimination, and brutality up close actually hope directly for the target, because that's something they have a first-hand way of thinking about. Lastly, the organizers tended to expect/ hope for things that were helpful to the marchers themselves, such as motivation, and stronger ties between the groups that had collaborated to put the march together.

4) Different people come to a protest, but nobody comes to a protest alone

And I mean nobody. There was a mean of 20 friends and a median of 10, with a few outlier organizers (or bad counters) who knew all the other organizers, and said they knew 100 people. I was excited about the question that got these numbers, but I'm still not entirely sure what to do with what it brought back. It could be seen as giving something like a threshold for engagement – how many people you need to know, before you'll go – but being observational, there are many obvious reasons to be wary of treating the numbers causally. Still. I find them intriguingly high.

An overwhelming number of people heard about it through some social means or another -- if not a friend, then facebook, or a group of which they were part. Only 17% of people didn't hear about it from a social source. Answers like "television" or "the newspaper" were almost unique and, interestingly if I'm not sure how, confined entirely to older, Black respondents.

I looked very hard for groups within the data, if with the careful tread that knows if you look for groups hard enough, you will find them. Most attempts did not work at all, which could be attributed to my skills as an analyst, the poverty of the sample, or the actual non-existence of sharply defined groups. The best clusters I found I plotted (above) but refuse to describe, out of fear people would stare at them until they saw something, which I am not confident is there. I am very pleased with my 3D plot though. [Note from the present: I can no longer even remember what these clusters represented.]

Sweeping up the last pieces, mean age was 32 and median was 28 (in our, we thought, older-than-usual group), but with people at both 13 and 74. There were more women than men. And while "student" was the single largest initial category, it was beaten by the aggregated "working class" category I cobbled together, not knowing what to do with "machine operator." This "working class" category was the single largest, then "student," and if you threw in teachers and professors, the people involved in education balanced the people who weren't just about 1:1.

And that's what we learned.

After chewing ardently on the collected data for some time -- multiway classification, principal components, factor analysis, k-means clustering, low-dimensional projections -- just looking at stuff and making a few tables told me pretty much everything I eventually knew (about, remember, 36 data points). What's more, I don't think that I found anything that would lead me to any major breakthroughs, such as a powerful but untapped demographic in the city, or an unexpected bifurcation of the activist community that is in need of immediate reconciliation (only, haha, expected ones). Still, the experience was enormously valuable, like, you know, most experiences. I feel significantly better prepared for the next protest, at which I will interrupt much more aggressively, move through the crowd systematically, and attempt an overall estimate of visible features such as body count and race breakdown, against which to gauge the representativeness of my ultimately collected samples. And, I will bring actual surveys.

In fact, maybe I'll just go print those out right now. [END]

In contemporary conclusion

I found this experience exhilarating, but not compelling enough to ever do it again, or to base my graduate studies on it. I continued to study social networks, always with the goal of mobilizing them on critical social issues, but protests themselves never really interested me – perhaps, in part because of this experience. The fact that so few marchers had a clear idea of what they even expected to accomplish made me fundamentally dismissive of the idea, even as I myself continued, and continue, to march. (I did the 2017 Women's March on crutches, thankyouverymuch.)

This might seem like a bad decision to make based on 36 freezing-cold Pennsylvanians, but the more I read about the Civil Rights Movement, the Black Panthers, about the Freedom Rides and sit-ins and boycotts, the more I actually felt vindicated in my position. We must – and I mean, must – now put forth a truly colossal amount of grassroots effort to thwart, overturn, and undo the generations of damage being done to us in this moment. But every successful movement has also known that marching, yelling – and then just going home – was not how victory was won.

But how is it won, then?

That's what I'll get in to next.