The Plan #5: A Flying Ottoman

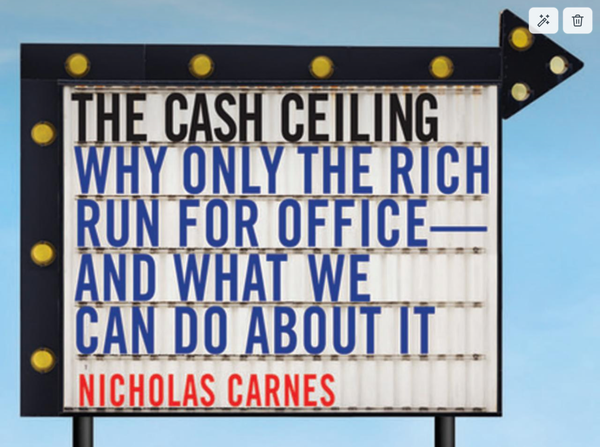

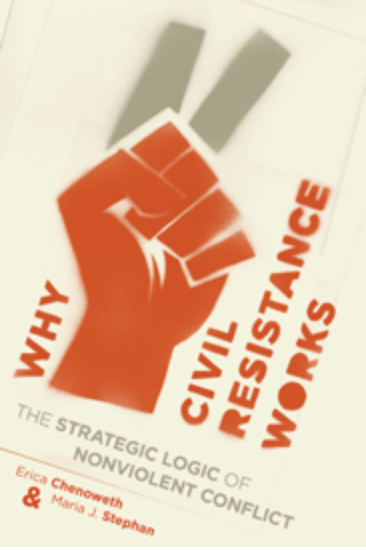

It is a job that I’m very proud of, and very fond of. When I accepted this job, I felt like it was one of the largest steps yet in the direction of my now twenty-year-old goal. In the years leading up to it, I had continued to look for the biggest problems I could find, while doing all sorts of unexpected things in the process. Getting too many degrees, starting companies, founding think tanks. I worked in public health, and tried to save children from brain damage. I worked in a middle school, and tried to save children from their classmates. I worked in Congress, and proposed establishing a center that used surveys to understand the human impacts of policies. Some of these thing worked. Some didn’t. (The congresswoman supported my legislation, but it was not to be.)

I kept moving, because I kept looking, because I refused to abandon my North Star. I would find, and solve, the most important problem in the world — and now finally, what better place to look than the National Science Foundation. I thought that perhaps, as I developed the tools to evaluate the research we funded, they would show me the way. I thought that the problem itself might even simply land on my desk one day.

But instead what happened was, as I prepared to set out on this brave new road, I suddenly saw that I already had all the pieces I needed. In the process of tumbling endlessly between fields and problems and places, of making what I thought was slow and painful progress towards becoming the person I hoped to be, I had picked up every one of the pieces I needed. I knew what the problem was. I knew how to solve it. And I just hadn’t realized it.

If this seems hard to believe, then let me tell a quick story.

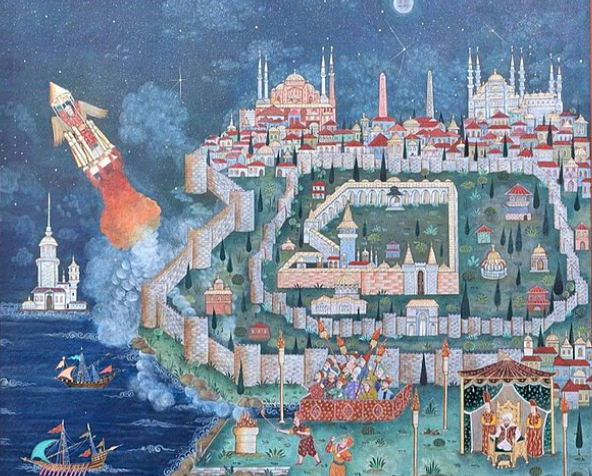

In 1633, the traveling gentleman Evliya Çelebi described a remarkable thing he had seen. The scientist, engineer, and now successful aviator Lagâri Hasan Çelebi, in a demonstration to the Ottoman Sultan Murad IV, strapped himself to a chair along with 140 pounds of gunpowder, and blasted himself into the ocean. He had to swim back to shore, but when he arrived, he was in good enough spirits to joke to the Sultan that Jesus sent his regards. This story was — appropriately — considered very funny.

Because of course, it had not happened. This was 296 years before “Rocket” Fritz von Opel was to complete the actual first manned rocket flight. At that earlier point in history, humans did not have the knowledge of thermodynamics, or solid state fuels, did not have the materials or the experience or in practically any respect the basic capacity to successfully accomplish such a thing. So why mention it? The point is that before Fritz, there was almost an entire three centuries during which humanity — with great, corroborated, historic, certainty — was still able to imagine a rocket that could safely carry a person. It was, given the state of things, a funny idea. But it still was an idea. Waiting.

The lesson I take from this — though of course I’m not the first — is that the difference between an idea being loony, or revolutionary, is often a rather simple matter of the tools available at the time. Do you have a theoretical model of computation? A functional language for expressing that computation? The ability to store digital information using more convenient tools than donut-shaped magnets inside of refrigerator-sized tanks full of olive oil? No? Then if you talk about a pocket-size device that can access six billion pages of information and send moving pictures instantly to anyone on the globe, people will walk in large circles to get around you on the sidewalk. But if you do have these pieces, if you have the components of personal computers and smartphones and the internet, then you can use them to define an entirely new age of history.

The same is true of “the most important problem in the world.” If you don’t have the right technology, the right statistics, the right survey tools, the right foundation of research, then you might as well just launch yourself into the ocean.

But for all its ridiculousness, this is still an idea that we dance around daily, and have for many years, peeking at it out of the corners of our eyes, half-embarrassed, half-hopeful. We talk about “doing good,” and we talk about safe, reasonable, not too ambitious ideas like “moving the needle,” and maybe even, though only with a knowing laugh at ourselves, we talk about “saving the world.” Like a 17th century Ottoman, telling stories that are so funny … unless they might be true?

The thing I want to show you is that — they might be. Now.

Now, at this point in history, in 2025 C.E., we do have the pieces. We have the data, and the methods, and the theory, we have the computational power, and the experimental results. Just like the three centuries it took humanity to turn a simple idea into a complicated fact, the mountainous pile of patterns and evidence and algorithms needed years, before my mind could even see they were part of a bigger picture. But they are. And we can put them all together, to solve the most important problem in the world.

So it’s time to start talking about what that problem is.

Subscribe to make sure you don't miss the next part!

And donate, to make sure I can stay alive to post it!