When I die, remember me for this

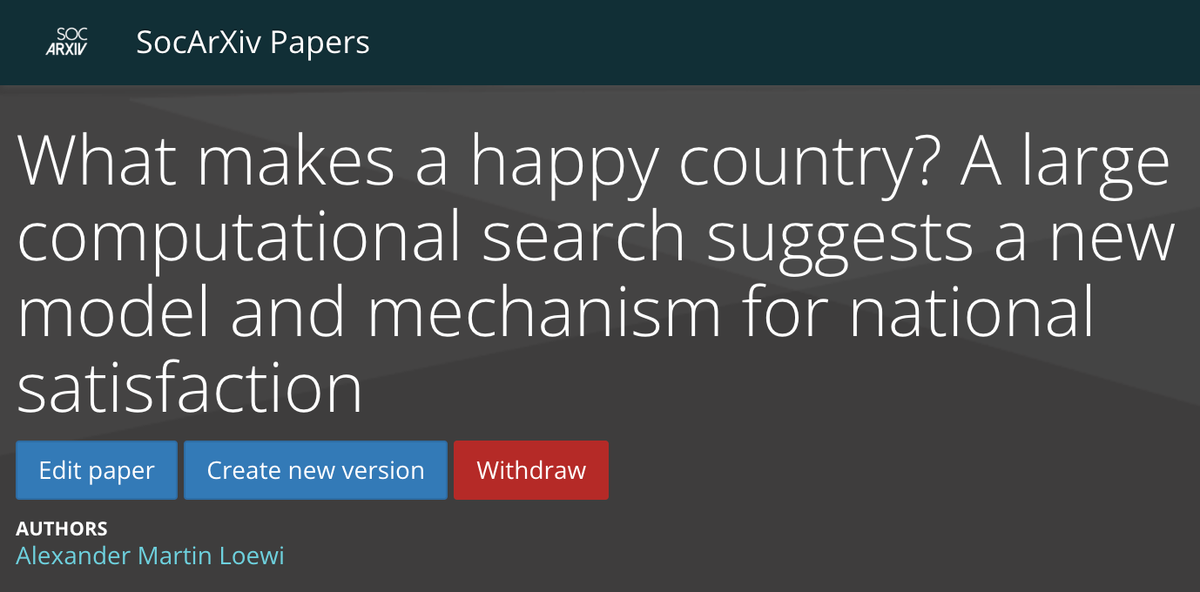

This morning I got an email with a very small notification. After a brief moderation check, my paper had been posted on SocArXiv. This wasn't a journal. It wasn't "published." But after close to three years of on and off work, no collaborators, no institutional support, and no funding, it was now a permanent part of the academic record. And I want to talk about it. Some, for myself. Some, for anyone who is trying to walk a similar path. But then, once that's all out of the way – for all of us. I'll explain soon enough.

Publishing, anything, anywhere, is miserable

In a way, I should have talked about this research much earlier. Or, you could say I've been talking about it all along, as it's come to be the lens through which I view most of the world. But for a long time I've been attempting to walk a bizarre tightrope of both pushing my work, and trying to save its first public appearance for a place that would have an impact. But you can't get a book deal without existing publicity, you can't get a news piece about research before that research is published, most journals take 6-12 months to publish, and you can't get an op-ed about something that has already been published elsewhere, including in blogs – so I've been painfully, slowly, and unproductively testing each of these doors in turn, before finally resigning myself to the need for academic publication. If I am to be seen as a researcher by the public, then that is the price I have to pay. And of all the cards I have to play, I believe that one is the best.

The other reason I haven't been talking about this research is that research isn't a good story on its own. I wanted to set the stage, lay the groundwork, and also respond to the truly unprecedented events of the day. I hope I've been able to do those things in an informative and entertaining way, but I wonder now if I shouldn't have just started from the top with the paper, anyway – because that's where it all comes from.

But enough about me.

What I set out to do

The answer here is an absolute onion, so let me try to lay it out as simply as possible. (I re-estimated the World Happiness Report's model of national satisfaction because (I doubted the model the second I saw it while (I was trying to do a program evaluation of the whole world after (I was inspired by program evaluation I did at the National Science Foundation but also (I had been looking my whole adult life for the greatest social impact I could possibly make, and this seemed to be the only rigorous way to find it)))))

At the beginning, anyway.

What I found

- The most widely known, widely published, widely accepted explanation of what makes a country happy is complete garbage. At best, a good-faith reheating of old, bad, assumptions. At worst, an intentionally misleading conclusion, presented through inexcusable statistical choices.

- The most likely answer is not GDP, but a collection of variables that fall into three broad categories: Survival Needs, Social Inclusion, and Societal Self-Determination. These are overwhelmingly and often explicitly composed of progressive priorities like LGBTQ+ social acceptance, gender equity, accessible political power, and more.

- The most recent Nobel in economics was awarded for a paper citing "institutions" as the true driver of what makes nations "fail." But in that paper, "failure" is used to mean "low-income." When you instead choose life satisfaction as your outcome, "Institutional" variables compose 5% of the total estimate, and variables that fit a pattern of anti-authoritarian psychology explain as much as 95% of the outcome.

- In conclusion, if we want better lives, then we must empower people who want us to have better lives. There is simply no other option. Not technology, not institutions, not the invisible hand, not the arc of the universe. We make a goal – we entrust power to the people who are most able to carry it out.

Why it matters

It sounds so simple, I know. Either so dumb, or so obvious. And yet, look around. Is this how we talk about the world? Is this how we pursue, or support, or nurture, or elect our leaders now? Is this the goal that we have, for ourselves, or our families, or our country? Who wakes up and says, in as many words, "How do I make the lives of people better today?" Who says, with anything other than delusional grandeur, "I have a clear, evidenced plan, for how to improve the very experience of life in this country?" If it is said, I do not hear it. If there is such I person, I do not know them.

If you were to argue that we don't need to say these things out loud to accomplish them well, I would agree with you to a point. But there are 340 million Americans. There are 8 billion people on the planet. I refuse quite flatly to accept that we can just wing this, based upon experiences and intuitions that we quickly realize clash violently with those of millions of other people. And any endeavor, of any scale, down to a single person, is more likely to succeed when it is explicit and intentional about what it attempts. So what should we attempt? Better lives. Because – and I mean this quite literally – what else is there? (A: A planet that won't eventually burst into flame beneath our feet, but for now let's just quietly assume that's part of the equation.)

So now what

Well – lots of things. Some I've already mentioned, some I'll mention soon. But I will leave you with a lesson that came after the research was done. When you make the most important thing your highest priority, the world falls into place behind it.

And Happy Juneteenth. Both because it happened before, and because it can happen again.