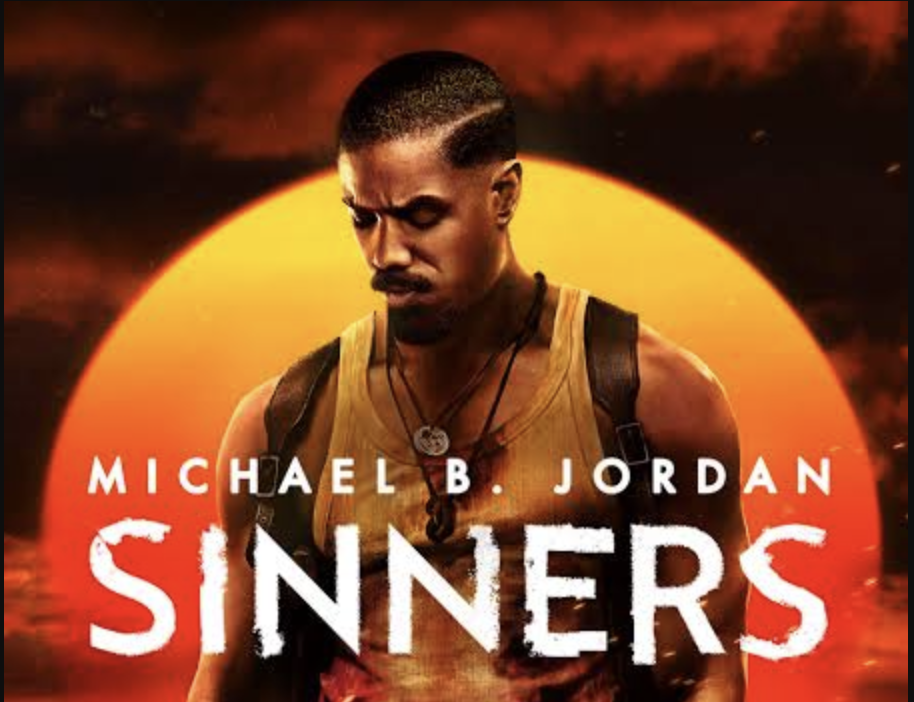

You Can be Angry - But You Can't Give Up. An Overthinking of Sinners.

The piece I'm working on – regarding the rationale to use when demanding the President's resignation – is taking more time and legal research than I anticipated. While that research progresses, I found that the meaning of this already record-breaking film is surprisingly relevant to our political situation. And of course, it's a banger.

MAJOR SPOILERS follow (for Sinners and Black Panther), which is my way of holding this essay hostage until you go see it for yourself.

I love Ryan Coogler

The place to start is that I've been acutely aware of Ryan Coogler ever since I saw the trailer for Fruitvale Station in 2013 and immediately decided I would never watch it. Not because it didn't look good, but because it looked too good, and consequently too painful. (The movie tells the true story of Oscar Grant being fatally shot, in the back, while lying on the ground, by transit police in the Bay Area.) But those ninety seconds made an indelible impression.

The first movie of his I dared watch was Creed, which remains an all-time favorite – one of those movies that makes you still root for the director, even if you don't like his subsequent work as much. He was the biggest reason I watched Black Panther, and I liked it, but it didn't stay with me in the same way – except for the villain.

Villain?

And by villain I mean Killmonger. I have to specify because there are other villains, but also because it's not entirely clear that he's supposed to be seen as a villain. His character is more charismatic than the protagonist's, he's played by Coogler's main actor muse Michael B. Jordan, at the end of the movie Black Panther basically does what Killmonger wanted to do (release secret technology to the world, though with humanitarian instead of genocidal applications), and he doesn't just get killed, but chooses to die an epic and narrated death, putting his money where Patrick Henry's mouth was:

Just bury me in the ocean with my ancestors that jumped from the ships, because they knew death was better than bondage.

Together, the film's message is unambiguous: The guy's got a point. Not like a Bond villain has a point sort of, but is still obviously Evil, Ugly, and Bad. But like no, listen, really – the guy's got a point. And he's not ugly – he's actually ripped, and has supercool traditional scarification.

But also, his name is "Killmonger." So – what's going on exactly?

Sinners tells an even more complex story

For those of you choosing to read this before watching the movie, I can't say I understand, but I will get you up to speed as fast as possible. Two brothers from the Delta have just returned home after working in Chicago for the mob. They start a juke joint, throw a huge opening night party, get invaded by vampires, and only one person makes it out alive (though two make it out dead). The End.

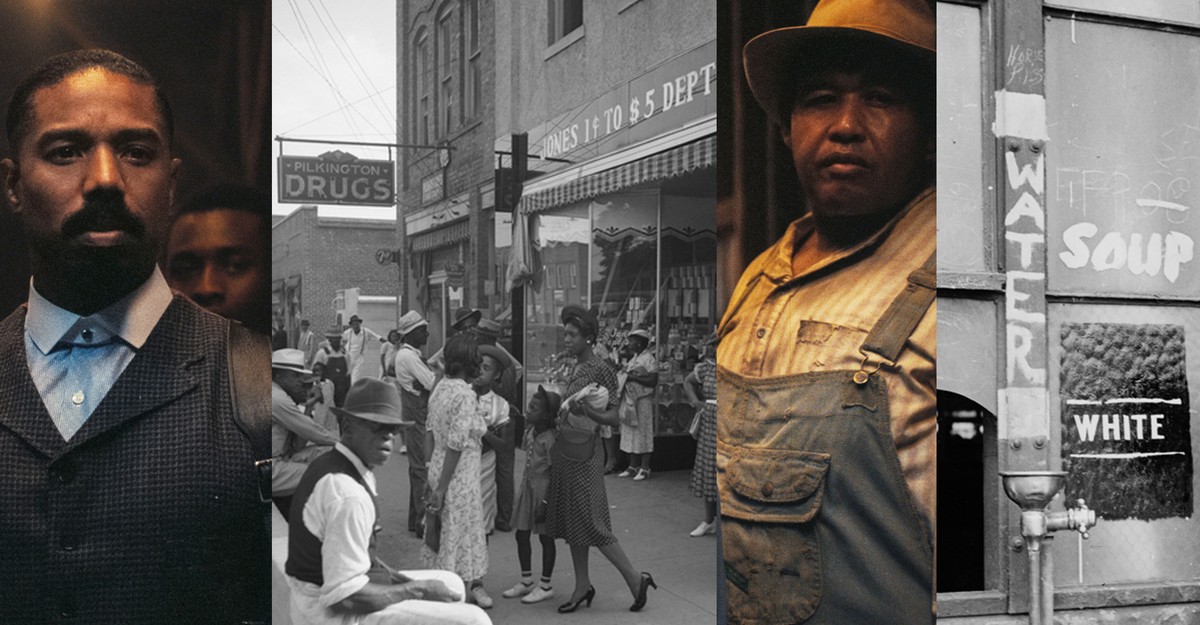

The complexity is not in the plot, but the moral – and it starts with the fact that the movie is almost nothing but villains, in a conventional sense. It's called Sinners for a reason. There are the main character mobsters, who shoot the knees off children for daring to rob them. There are the alcoholic musician, the philandering singer, and the preacher-father-defying son – and these are the good guys. Though the only unambiguous villains are the Klan, which is demonstrated by tommy-gunning them to death in vast numbers in classic Hollywood Nazi-slaughtering fashion. And you won't get much complaint from me.

But then there are the vampires.

The undead make a strong case

The vampires are vampires in the important, familiar ways – they bite people, and those people also turn into vampires. The unexpected twist is that they quickly bite enough people to form a large, seemingly harmonious, multiracial coalition, with a rad soundtrack – hellbent on destroying the living not just because they are alive, but because of the sins they have committed, and saving their own oppressed friends into eternal life. They promise power, immortality, and revenge – and based on the way they look 60 years later (in movie time), they aren't lying.

In other words, they present an offer that looks so appealing, I am convinced that Coogler had to make them visually grotesque just so that the audience wouldn't mistake them for the real good guys. Because once again, you had to admit – especially in Mississippi in 1932 – it seemed like they had a point.

I saw Coogler handing me the same complex moral conclusion, and I still didn't know what to do with it. But I thought that the key might be in trying to understand what exactly the vampires are supposed to represent.

I fear that I shall never see, a decent vampire simile

They defy any trivial explanation. For example they are not just White People, because there are soon Black and Chinese vampires. They are not just Bad People because the Klan exists separately - there's no need for an independent symbol of simple evil. And they're not even just people who take things from you (like your culture or here most prominently, music) because being taken from doesn't make you a taker, or friends with those who did the taking.

There is a strong argument that through their violent consumption, they most represent forcible cultural assimilation and appropriation. All the people bitten by the Irish vampire start singing Irish songs, and the ones who first recognize the vampire for what he is are the Choctaw. The thing the vampires really want from the juke joint crowd is the music. But I think that leaves out the most important question: what is the nature of the culture into which they assimilate people?

I first thought that the answer might be Bitterness, or Despair. The vampires represented people who were abused (the first Irish vampire's country was crushed by the British, the Black sharecroppers were still living under Jim Crow), and who tragically but understandably became overwhelmed by spite and joined a vast crusade to punish the sinners who had done this to them – like Killmonger wanted to do. But this didn't quite fit, because together, they were still presented as joyful, if ghoulish, in the Dropkick Murphys From Hell scene that I will be rewatching every few months until I die.

I'm even more tempted to say that the culture was simply a culture of conformity and consumption – but at best, this didn't feel complete. Why? What was behind that drive? (And in the post-credits scene, the vampires seem to present a self-assured individualism, much more than conformity anyway.)

What I believe, now

Many people are writing very good interpretations of this movie, which is itself a testament to its quality. Below are just a few. And the more I think and read about it, the more conflicted I am about my own reading. So rather than claim this is definitive, I will simply say that I eventually came to see an incredibly strong allegory in Sinners, and one that speaks deeply to me, and this moment. That is the one I will describe.

Vampirism of meaning

Eventually I found my way to the meaning I knew had resonated with me: nihilism. The vampires are the people who have given up on life.

This also made their viral nature fit better. Nihilism travels, and even against the will of those affected. If everyone around you says that there's no hope (or bites you on the neck), you don't need to feel that emotionally, right away – you can simply start by taking it as a statement of fact. The rest follows.

If you interpret nihilism as a choice, then this seems to ignore the fact that nobody chooses to become a vampire. But Coogler shows that people can still be tempted towards the people they know they should stay away from – and don't recognize the true consequences until it's too late. I feel the same can be said of nihilism. No one is born believing nothing matters. No one wants to believe it. There must be forces that pull, and then push them there.

And of course, there's the terrifically literal connection: the vampires are the people who have given up on not just the living, but on life itself.

This leaves them carefree from the heavy bonds of earthly responsibility, but able only to take from those who continue to toil. The story they tell is honestly compelling, but the righteousness of their crusade against all sinners is complicated by the fact that this actually means all people – and the ultimately damning case against them is that those who go down that path are ultimately not as happy as they would have been, had they kept the company of mortals (as seen by Michael B. Jordan Number 2 saying that despite his immortality, he can never be as happy as when his brother was alive).

In initial conclusion

In other words, I came to believe that Coogler was saying:

I know that there are a million reasons you might want to give up – but don't. Yes you would have company, and fun. Yes they make strong arguments and honestly I understand them myself. But your life will be worse. And you will make things worse. And we remain alive in order to make things better.

Despite it all

Even though – and I believe this is an absolutely key part of the movie – things are really really bad.

I walked out of the movie shaken, not by the vampires but by the fact that all but one of the central characters was dead. I had grown attached to each of them, only for them to be shot stabbed eaten or set on fire. It felt as though someone had shown me something beautiful, just to tear it up and throw it at my feet. I did not enjoy the experience. But it also made me think of another one of my favorite story tellers – Colson Whitehead. Who tells many whimsical tales of disaster and pluck, but in The Underground Railroad, tells a story of unrelenting cruelty and slaughter from the first page to the last. (Buy it here! I'll make like – fifty cents!)

I can't honestly say I "enjoyed" The Underground Railroad either (or Anora, a film about the abuses of the rich by another director I love, which was excellent but that I would not watch again for love or money) – but I also appreciate that I wasn't supposed to "enjoy" it. And the fact that somebody made something so good that I watched it even though I came out feeling mostly battered is something that I truly respect. This is because getting even a glimpse, or just being reminded in a safe place of the sheer emotional scale of the things we face, is absolutely vital. Especially if you're going to have a chance of truly facing it – and not giving in to the seduction of giving up.

Remember this is from a director whose first feature film was about a detained man being shot in the back. He wants you to know how bad things are. Because only when you've seen that can you understand the seductiveness of the bad way out. Only then do his villains make sense.

In actual conclusion

This, to me, was the true and complete moral of the story: They will try – and in fact, they may succeed – in destroying everything that matters to you. But you simply cannot let that stop you. Sixty years later, the night of the vampires was still the best night of the one survivor's life. (Cast brilliantly as National Medal of Arts winner Buddy Guy, born in Louisiana just four years after the movie takes place.) It doesn't matter that they'll take it all away. If anything, that's just more reason to try to build the world you want, now.

And of course – that's how I feel. That's why this is not just a movie to me, that's why I'm writing about it in between pieces on legal precedents for treason. Because I see nihilism about our country everywhere, in honestly funny jokes and perfectly accurate observations, from smart and well meaning people. In demands that are so small they wouldn't solve the problem – or in a failure to demand anything at all. I understand. But it's just not the right answer. It's the way of the vampires. You cannot let in even one.

There's much more to the movie too, and many more threads to what I see as Coogler's core narratives as an artist. Michael B. Jordan Number 1 telling Miles Caton to move to the all-Black town vs. his brother's relationship with Hailee Steinfeld mirrors Black Panther's initial choice to keep Wakanda secret, against Killmonger's desire to engage with the wider world. There's the enormous symbolism of music and culture, including the suggestion that to give up on life really means to give up on creating things for yourself – or at least for people who appreciate you (the gray areas of which drive the conflicts around isolationism). I've largely skated over this, even though I am 100% ready for a story about how guitars can defeat the undead. But I've said more than enough already.

In conclusion, I hated Sinners. You should really go see it.